Five Counties Immigrants and Their Struggle Against 19th-Century Racism

In May 1869, as the golden spike was driven into the final rail of America’s first Transcontinental Railroad, marking a historic moment that symbolized progress and unity, a painful omission cast a long shadow over the celebration. The Chinese laborers who had built the most treacherous stretches of the Central Pacific Railroad were nowhere to be seen. Despite their backbreaking work carving through mountains and laying tracks across scorching deserts, they were excluded from the ceremony—erased not only from photographs and speeches but from the official memory of a nation they helped build.

That exclusion was not an accident. It was a harbinger of what was to come—a wave of institutionalized racism that would culminate in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and spread like wildfire across North America, Australia, and beyond. But amid this era of widespread hostility and legal oppression, some voices refused to stay silent.

Among those voices were two remarkable figures from the Five Counties (Wuyi) region of Guangdong province—Wu Tingfang and Mei Guangda. Like the thousands of Five Counties immigrants who crossed oceans in search of opportunity, they too faced discrimination, displacement, and injustice. Yet, rather than retreat, they rose to become powerful advocates for the rights of overseas Chinese during a time when such advocacy was rare—and often unwelcome.

Wu Tingfang, a Western-educated lawyer and diplomat, stood before the halls of power in Washington, D.C., armed with treaties, international law, and unyielding conviction. Mei Guangda, a respected businessman and community leader in Australia, fought tirelessly on the ground, defending individual immigrants and appealing directly to both colonial authorities and the Qing government for protection.

Their lives represent more than just personal journeys—they are testaments to the resilience and moral courage of Five Counties immigrants who dared to challenge systemic racism long before it became a global cause. In a world that sought to silence them, Wu Tingfang and Mei Guangda chose to speak out.

This is their story.

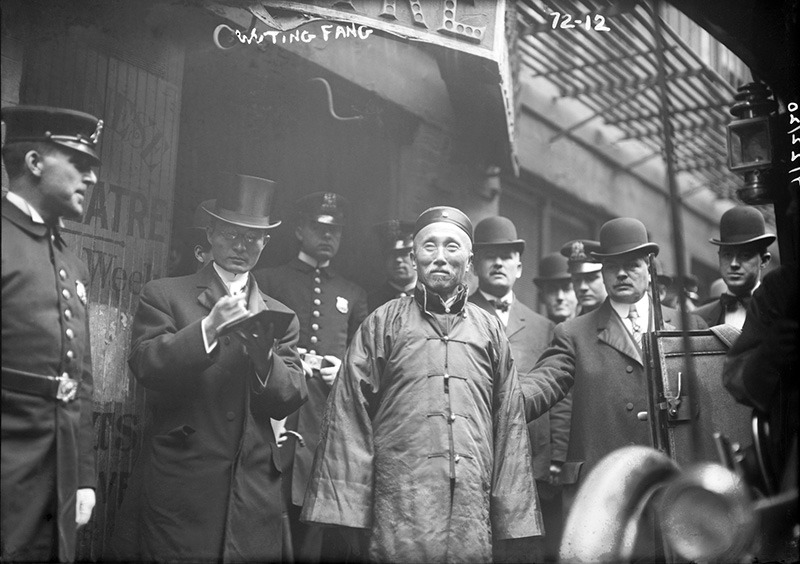

Wu Tingfang: A Diplomat Fighting for Justice in America

Among the many Five Counties immigrants who left Guangdong in search of opportunity, few rose to such prominence or wielded such influence as Wu Tingfang. Born in 1842 in Singapore to a family originally from Xinhui—one of the Five Counties—Wu’s life took him across continents, from Southeast Asia to China, and eventually to Britain and the United States. Educated in Western law and deeply connected to his Chinese roots, he became a pioneering diplomat and lawyer who stood at the forefront of defending overseas Chinese rights during one of the most hostile periods in their history.

As China’s Minister to the United States, Mexico, Peru, and Cuba in two separate terms, Wu Tingfang was not just representing a nation—he was advocating for an entire diaspora. The Five Counties immigrants, who had built railroads, mined gold, and contributed to American industry, were increasingly viewed with suspicion and hostility. Laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act marked the beginning of official discrimination against Chinese laborers. Wu Tingfang understood this all too well. As a man of mixed identity—rooted in both East and West—he used every tool at his disposal to challenge these injustices.

Defending Against the Expansion of the Chinese Exclusion Act

One of Wu Tingfang’s most significant battles was his opposition to the extension and expansion of the Chinese Exclusion Act. By 1901, the original law—which banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States—was due to expire. But instead of allowing it to lapse, anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States led lawmakers to push for its renewal—and even its application to newly acquired territories like Hawaii and the Philippines.

Wu Tingfang responded with a fifty-eight-page diplomatic protest, one of the most detailed and forceful documents ever submitted by a Chinese envoy. He argued that the Act violated international treaties and basic human rights. He reminded the U.S. government that China had repeatedly compromised in the name of diplomacy, only to be met with increasing hostility. He warned that if the United States continued down this path, China might respond by imposing higher tariffs on American goods, restricting the entry of American missionaries, engineers, and businesspeople, and reconsidering its openness to foreign investment.

Though the U.S. Congress ignored his warnings and passed the extended Exclusion Act in 1902, Wu’s arguments were widely recognized as some of the strongest legal and moral defenses of Chinese immigrants at the time.

Challenging Discrimination in U.S. Territories: Hawaii and the Philippines

Wu Tingfang did not stop at mainland America. When the United States annexed Hawaii in 1898, thousands of Chinese already lived there—many of them Five Counties immigrants who had migrated earlier under more open policies. The United States quickly moved to apply the Exclusion Act to Hawaii, barring new Chinese arrivals and restricting movement between the islands and the mainland.

Wu protested immediately. He reminded the United States that many Chinese in Hawaii were either born there or had been naturalized under previous agreements. He emphasized that these individuals were law-abiding, hardworking members of society who posed no threat. He also invoked international law, stating that any change in policy should require consultation with affected parties—in this case, China.

Similarly, when the United States imposed exclusionary policies on the Philippines after seizing control from Spain, Wu again stepped in. He condemned the unilateral nature of the decision and demanded that the United States honor its treaty obligations. Though his protests did not halt the spread of exclusion laws, they ensured that China’s voice was heard—and respected—on the global stage.

Building Public Support and Shaping Perception

Wu Tingfang knew that diplomacy wasn’t only about treaties and formal protests—it was also about perception. He actively engaged with the American public through speeches, articles, and interviews, using platforms like The North American Review to share a more nuanced view of China and its people.

He spoke passionately about the importance of mutual respect and cultural understanding. He highlighted the long history of Chinese civilization and urged Americans to see Chinese immigrants not as threats, but as contributors to economic growth and social progress.

His efforts helped shift the views of some influential figures, including former U.S. Secretary of State John W. Foster, who publicly criticized the Exclusion Act and supported Wu’s calls for fair treatment of Chinese immigrants.

Legacy of a Trailblazer

While Wu Tingfang could not overturn the tide of institutional racism, his work laid the foundation for future generations of diplomats and advocates. He gave voice to the voiceless and defended the dignity of the Five Counties immigrants who had built so much of America’s infrastructure yet remained unrecognized.

As a lawyer, diplomat, and advocate, Wu Tingfang embodied the resilience of overseas Chinese. His legacy lives on—not only in the annals of Chinese diplomacy but also in the ongoing struggle for justice, equity, and inclusion for all immigrant communities.

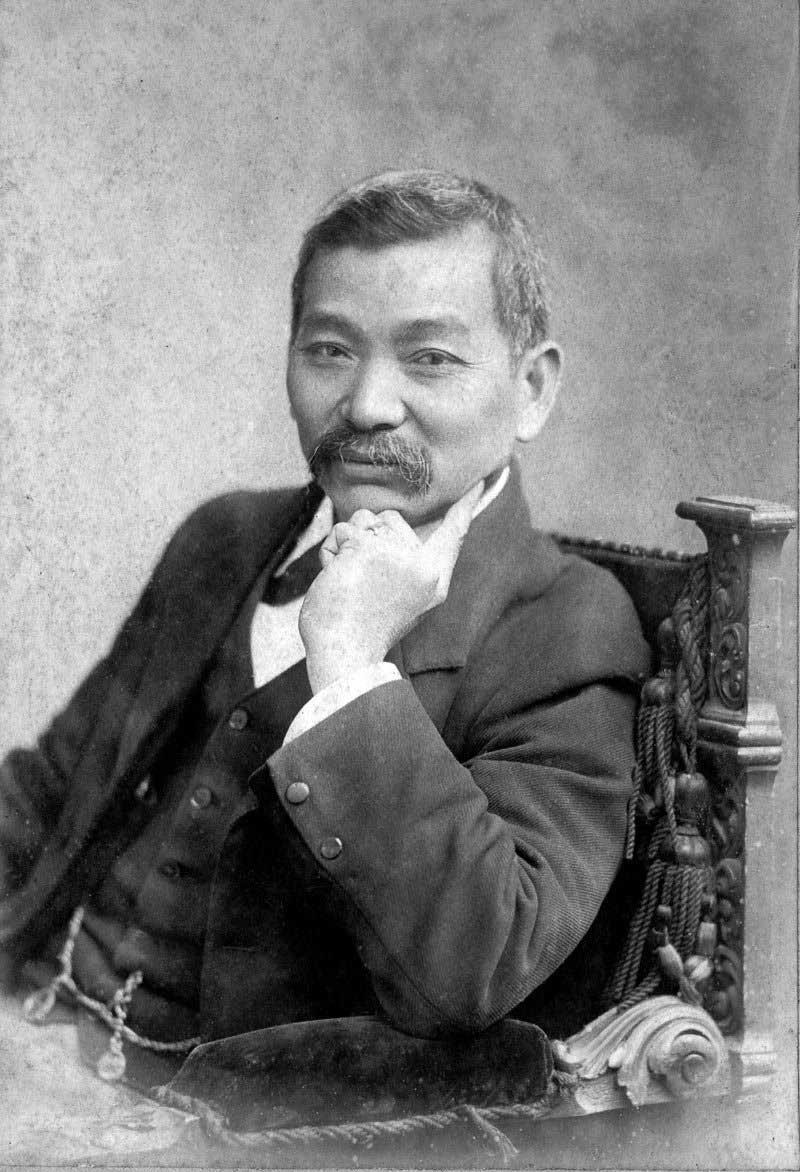

Mei Guangda: A Community Leader Defending Chinese Rights in Australia

If Wu Tingfang fought for Chinese rights from the halls of power, Mei Guangda (Mei Quong Tart) waged his battle on the streets, in courtrooms, and through relentless appeals to both colonial and Qing authorities.

Born in Taishan—then known as Xinning County—in 1850, Mei Guangda was part of the early wave of Five Counties immigrants who arrived in Australia seeking fortune during the gold rush era.

At just nine years old, Mei immigrated to New South Wales, where he was adopted by an English mining family. Through hard work and determination, he learned English, converted to Christianity, and received a Western education. Eventually, he became a successful businessman and landowner—but never forgot the struggles of his fellow Chinese immigrants.

As Australia’s racial climate worsened in the late nineteenth century, Mei Guangda emerged as a tireless advocate for Chinese Australians, standing up against the rising tide of the White Australia Policy and fighting for legal protections for his community.

Battling Institutional Racism in Colonial Australia

Australia’s anti-Chinese sentiment grew rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. After initial tolerance during the gold rush, local governments began passing restrictive immigration laws. By 1888, the infamous White Australia Policy was taking shape, severely limiting Chinese immigration and mistreating existing residents.

Mei Guangda resisted these policies at every turn. He personally helped Chinese immigrants facing unjust treatment at ports or under discriminatory laws. He also appealed directly to British authorities, arguing that Australia’s actions violated Sino-British treaties that guaranteed free movement of Chinese citizens.

In one notable case, Mei intervened when a ship carrying dozens of Chinese passengers was denied entry to Sydney due to false accusations of document fraud. Working alongside other community leaders, he challenged the decision in court—and won. Hundreds of Chinese immigrants were finally allowed to disembark.

Advocating for Consular Protection in Australia

Recognizing that Chinese immigrants lacked legal representation, Mei Guangda lobbied the Qing government to establish consulates in Sydney and Melbourne. He believed that having official diplomatic presence would provide essential protection for Chinese nationals facing abuse or unfair treatment.

He traveled to China twice to meet with officials like Zhang Zhidong, presenting detailed reports on the plight of Chinese Australians and urging action. Although the Qing government was slow to respond, Mei’s persistence eventually led to the establishment of consulates in Australia—marking a turning point for Chinese diplomatic engagement abroad.

A Legacy of Compassion and Courage

Beyond politics and law, Mei Guangda was known for his deep sense of compassion. He funded schools, churches, and charitable causes, and was widely respected by both Chinese and Australian communities. Poets and public figures praised him for his integrity, generosity, and unwavering commitment to justice.

When he died in 1903, over three thousand mourners attended his funeral in Sydney—an unprecedented turnout for a Chinese Australian at the time. Australian newspapers hailed him as a great son of China and a model citizen.

Connecting Their Struggles to the Larger Narrative

The stories of Wu Tingfang and Mei Guangda are not just individual tales of heroism—they are representative of a broader pattern of resistance among Five Counties immigrants around the world. Whether in the United States, Australia, or Latin America, these immigrants faced brutal working conditions, legal barriers, and systemic racism. Yet, they did not remain silent.

Through diplomacy, activism, and grassroots leadership, figures like Wu and Mei carved paths of resistance and resilience. They showed that even in the face of overwhelming odds, one voice could make a difference—and that collective struggle could plant seeds for future change.

Lessons for Today

The historical omission of Chinese railroad workers at Promontory Summit was not just an oversight—it was a symptom of deeper societal biases that persisted for decades. But thanks to advocates like Wu Tingfang and Mei Guangda, the voices of overseas Chinese were not entirely silenced.

Today, as debates around immigration, race, and belonging continue, their legacies offer valuable lessons. They remind us that the fight for justice is rarely easy—but always worth pursuing. And they challenge us to remember those whose contributions have gone unseen, whose sacrifices have gone unacknowledged, and whose stories deserve to be told.

The journey of the Five Counties immigrants is far from over. It continues in the hearts and minds of those who believe in fairness, dignity, and the enduring power of human resilience.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.