Why Guangdong’s Marriage Traditions Start with Candy in Elevators (And a 3-Day Rule)

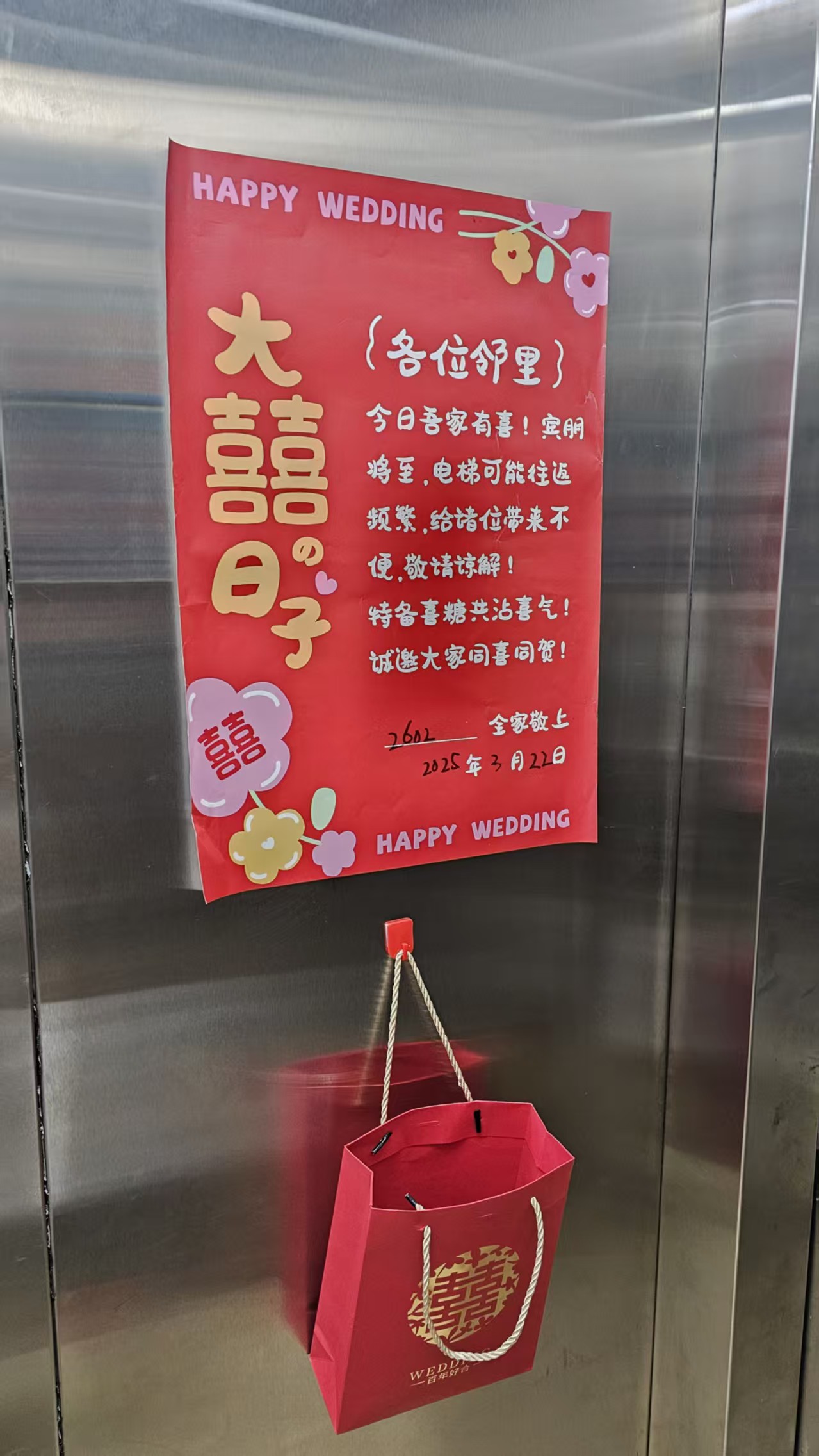

I was in the elevator this morning, rushing to grab my coffee before work, when I noticed something unusual—a small bag of candies tied with a red ribbon and a handwritten note that read:

DEAR NEIGHBORS,TODAY, OUR FAMILY IS CELEBRATING A JOYOUS OCCASION, AND GUESTS WILL BE ARRIVING. THE ELEVATOR MAY BE USED FREQUENTLY, WHICH MIGHT CAUSE INCONVENIENCE TO EVERYONE—PLEASE FORGIVE US. WE’VE PREPARED WEDDING CANDIES TO SHARE THE JOY, AND WE SINCERELY INVITE EVERYONE TO CELEBRATE WITH US!”

–NEWLYWED COUPLE ON THE 26TH FLOOR

It made me smile—not just because of the thoughtful gesture but also because it reminded me of how deeply rooted these traditions are in Chinese culture. That little bag of candy wasn’t just sugar; it carried centuries of history, symbolism, and familial love tied to Guangdong’s marriage traditions . It got me thinking about the intricate customs that define weddings in this southern province, where rituals like this have been practiced for generations.

The Elevator Candy Mystery: Symbolism in Guangdong’s Marriage Traditions

You might wonder why the newlyweds left candy in the elevator. In Guangdong’s marriage traditions , sharing sweets is no ordinary act—it’s packed with meaning. The word for “sweet” (tian , 甜) sounds like “filling,” so giving out candies symbolizes filling life with happiness and prosperity. This custom stems from the broader tradition of Guo Da Li (过大礼), or the grand gift exchange between families before the wedding. Picture this: baskets overflowing with dragon-phoenix cakes (Long Feng Bing ), coconuts representing unity within the family (“有爷有子”), and pomegranates promising fertility. Each item isn’t random—it’s carefully chosen to ensure auspicious beginnings.

But back to the elevator…those candies aren’t just treats; they’re an invitation for the community to celebrate together. And if you think about it, what better way to introduce yourself as newlyweds than by spreading sweetness?

A Bride’s Journey Through Time: From Blind Marriages to Modern Choices

Imagine being a bride in late Qing Dynasty Guangdong. Your parents arrange everything—from matching birth dates (Sheng Chen Ba Zi ) to selecting the perfect day for the wedding. You might even endure Mang Hun Ya Jia (盲婚哑嫁), or blind marriages, where you don’t see your groom until the ceremony itself. Sounds daunting, right? For many women at the time, marriage meant leaving their own family behind forever, marked by rituals like crying farewell during Ku Jia (哭嫁).

Fast forward to the 20th century, and things start changing dramatically. During the Republican Era, Western influences trickle into cities like Guangzhou. Suddenly, brides wear white dresses alongside traditional red ones, and couples exchange rings instead of relying solely on ancestral blessings. By the time the People’s Republic of China is founded in 1949, laws abolish arranged marriages and promote gender equality. Today, young women in Guangdong can choose their partners freely, balancing careers and family life without sacrificing either.

Still, echoes of the past remain. Take Jing Cha (敬茶), for example—the tea-serving ritual where newlyweds bow to elders and express gratitude. While some may view it as old-fashioned, others see it as a beautiful reminder of family bonds. One friend told me her favorite part of her wedding was serving tea to her grandmother, who whispered stories of her own marriage days long gone. These moments connect generations, bridging the gap between tradition and modernity.

Closing the Circle: Returning to the Wife’s Family on the Third Day

One of the most poignant rituals in Guangdong’s marriage traditions happens after the main ceremonies are over—the “returning to the wife’s family” (Hui Men , 回门). On the third day of marriage, the newlyweds visit the bride’s parents’ home, bringing gifts such as roasted pig (Shao Zhu , 烧猪), which symbolizes the bride’s purity and the union’s success. This visit marks the official end of the wedding celebrations and signifies the couple’s commitment to maintaining strong ties with both sides of the family.

For many families, Hui Men is a joyful occasion filled with feasting and laughter. It’s also a chance for the groom to formally thank his in-laws for raising their daughter and to demonstrate his respect and dedication to the new family he has joined. The roasted pig, in particular, holds deep significance—it’s a tangible representation of harmony and prosperity, ensuring that the marriage begins on solid ground.

In modern times, this ritual has taken on additional layers of meaning. With urbanization and migration becoming increasingly common, Hui Men often doubles as a reunion for extended families scattered across cities or even countries. For overseas Chinese communities, it’s an opportunity to reconnect with cultural roots and reinforce the importance of filial piety, even in faraway lands.

The Dragon-Phoenix Dance: Rituals That Stand the Test of Time

Now imagine walking into a bustling banquet hall in Guangzhou. Red lanterns hang overhead, tables groan under mountains of food, and everyone wears their finest clothes. At the center stands the bride, resplendent in her Long Feng Gua (龙凤褂), an embroidered gown adorned with dragons and phoenixes—a timeless symbol of harmony and good fortune.

This iconic dress represents much more than fashion. Historically, only wealthy families could afford such elaborate attire, making it both a status symbol and a blessing for the future. Even now, brides proudly wear them, though often paired with Western-style veils or tiaras—a nod to globalization’s influence.

Another unforgettable moment? The search for the red shoes (Zhao Hong Xie , 找红鞋). Legend has it that hiding the bride’s red shoes tests the groom’s sincerity. When he finally finds them, slipping them onto her feet signifies his commitment to care for her throughout their lives. Watching this playful yet profound ritual unfold feels like witnessing magic—a blend of fun and deep cultural significance.

From Rural Villages to Urban Skyscrapers: How Modern Life Shapes Guangdong’s Marriage Traditions

Let’s rewind again—to rural Guangdong villages decades ago. There, weddings were multi-day affairs filled with feasts, fireworks, and endless ceremonies. Elders played matchmaker, and entire communities gathered to witness the union. Fast forward to today, and urban professionals opt for sleek hotel banquets or intimate destination weddings. Some even skip traditional rituals altogether, choosing instead to livestream their vows via social media platforms like Douyin (TikTok).

Yet despite these changes, certain elements persist. For instance, the role of the Da Jin Jie (大妗姐)—a female wedding coordinator—is still cherished, though now she might use apps to streamline logistics. Or consider the resurgence of interest in intangible cultural heritage: museums like Foshan’s Jia Qu Wu showcase restored bridal chambers, allowing visitors to experience historical ceremonies firsthand.

Even government policies play a role. Recent reforms aim to curb excessive bride prices (Cai Li ) and encourage simpler, more meaningful celebrations. Cities like Guangzhou have introduced outdoor registration points surrounded by lush gardens, offering couples a serene alternative to crowded offices.

Gender Roles: Breaking Free While Honoring the Past

Traditionally, Guangdong’s marriage traditions reinforced strict gender roles. Men provided for the family, while women managed household duties. But times are changing. Young couples increasingly share responsibilities, from planning the wedding to raising children. My cousin Mei recently joked that her husband spent more time researching baby strollers than she did—a far cry from the days when fathers rarely participated in childcare.

That said, challenges remain. In some rural areas, preferences for male heirs linger, though attitudes are shifting thanks to education campaigns and economic development. Meanwhile, urban women navigate the delicate balance between honoring tradition (like serving tea to elders) and asserting independence (like pursuing careers after marriage).

One particularly inspiring trend? Women reclaiming once-controversial practices. Remember Ku Jia (哭嫁)? What used to be a painful farewell has transformed into a celebratory performance, empowering brides to express themselves creatively.

Bridging Generations, Cultures, and Hearts

As I stepped off the elevator with my handful of candy, I couldn’t help but reflect on how Guangdong’s marriage traditions continue to evolve. These customs are like a river—they flow through history, adapting to new landscapes while retaining their essence. Whether it’s a bride wearing a dragon-phoenix gown, a groom searching for hidden red shoes, or neighbors sharing sweets in celebration, each moment connects us to something greater: the enduring power of family, love, and culture.

And then there’s Hui Men —that final act of returning to the bride’s family, closing the circle of gratitude and unity. It reminds us that no matter how far we travel or how much the world changes, the bonds of family will always anchor us.

So next time you find yourself in an elevator—or anywhere else—take a closer look at those seemingly simple gestures. They might just hold the key to understanding centuries of wisdom wrapped up in a single sweet bite.

FAQ: Guangdong’s Marriage Traditions

Guangdong’s marriage traditions include rituals like Guo Da Li (过大礼), An Chuang (安床), Shang Tou (上头), and Jing Cha (敬茶). These customs emphasize family harmony, auspicious symbolism, and cultural heritage. For example, gifts such as dragon-phoenix cakes and coconuts symbolize prosperity and unity.

Unlike northern regions with high bride prices (Cai Li), Guangdong’s marriage traditions focus more on symbolic gestures and meaningful rituals. Additionally, Guangdong weddings often blend traditional practices like Hui Men (回门) with modern influences, showcasing a balance between heritage and innovation.

The Long Feng Gua (龙凤褂), or dragon-phoenix gown, is a traditional bridal dress adorned with intricate embroidery. It symbolizes harmony, good fortune, and prosperity, making it an essential part of Guangdong’s marriage traditions.

Globalization has introduced Western elements such as white dresses, ring exchanges, and destination weddings into Guangdong’s marriage customs. However, core rituals like Jing Cha (serving tea to elders) and symbolic items like the Zi Sun Tong (子孙桶) remain deeply rooted in tradition.

The Hui Men ritual involves the newlyweds visiting the bride’s family on the third day of marriage, bringing gifts like roasted pig to symbolize purity and success. This tradition highlights the importance of maintaining strong ties with both families.

Yes! For example, the Chaozhou-Shantou region is known for Ku Jia (哭嫁), where brides express emotional farewells through crying. Meanwhile, Hakka communities prioritize simplicity, focusing on practical rituals rather than extravagant displays.

Historically, Guangdong’s marriage customs reinforced strict gender roles, with men as breadwinners and women managing households. Today, however, younger generations increasingly share responsibilities, though challenges like lingering inequality persist, especially in rural areas.

The Da Jin Jie is a female wedding coordinator who ensures smooth transitions between rituals. In modern times, this role has adapted to include organizing hybrid ceremonies that combine traditional and contemporary elements.

Urbanization has led to simplified wedding processes, with many couples opting for sleek hotel banquets or intimate ceremonies. Despite this, core traditions like Guo Da Li and Jing Cha continue to be celebrated, albeit in streamlined forms.

The Chinese government has implemented measures to curb excessive bride prices and promote simpler, more meaningful celebrations. For instance, Guangdong’s “marriage reform experimental zones” encourage collective weddings and eco-friendly practices.

The red umbrella is a symbol of protection and good fortune. Brides traditionally hold it during the procession to shield themselves from evil spirits, reflecting the deep-rooted belief in auspicious symbolism within Guangdong’s marriage traditions.

Food plays a central role in Guangdong weddings, with feasts featuring dishes like roasted pig, abalone, and glutinous rice cakes. These foods carry symbolic meanings, such as prosperity, fertility, and happiness, reinforcing the cultural significance of the event.

Symbolic items include Zi Sun Tong (子孙桶, a wooden bucket for washing newborns), Hong Chi (红尺, a red ruler symbolizing vast farmland), and pomegranates (象征多子多福). Each item reflects hopes for prosperity, lineage continuation, and marital bliss.

Historical events like the Republican Era reforms and post-1949 legal changes significantly influenced Guangdong’s marriage customs. For example, the 1950 Marriage Law abolished arranged marriages and promoted gender equality, reshaping traditional practices.

In the Zhao Hong Xie (找红鞋) ritual, the groom searches for the bride’s hidden red shoes and places them on her feet. This playful yet meaningful act symbolizes his commitment to caring for her throughout their lives.

Modern trends include themed weddings, digital invitations, and livestreamed ceremonies. Couples also incorporate personalized touches, such as custom-designed Long Feng Gua gowns and eco-friendly decorations.

Technology has transformed how couples meet and plan weddings. Online platforms facilitate matchmaking, while social media inspires creative ideas for ceremonies. Even traditional rituals like Jing Cha are now shared via apps for remote participation.

Sharing sweets, such as candies or dragon-phoenix cakes, symbolizes spreading happiness and prosperity. This gesture connects neighbors and guests to the joyous occasion, reinforcing community bonds.

You can visit cultural heritage sites like Foshan’s Jia Qu Wu museum or attend local festivals celebrating traditional weddings. Many cities also offer immersive experiences, such as reenactments of ancient rituals.

Guangdong’s marriage traditions stand out due to their rich symbolism, regional diversity, and adaptability. From the intricate San Shu Liu Li (三书六礼) framework to unique practices like Ku Jia, these customs reflect the province’s vibrant cultural identity.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.