Feng Ru of Enping: The Chinese Wright Brother You’ve Never Heard Of

ucked in the hills of Guangzhou’s Huanghuagang Cemetery, beside the tombs of seventy-two revolutionary martyrs, rests a name few today recognize—yet one that once soared across continents. Feng Ru (冯如), born in 1884 in the humble village of Xingwei, Enping (恩平杏围村), carved his place in history as the first Chinese aviator and aircraft engineer. He is remembered not only for taking to the skies, but for lifting a nation’s aspirations with him.

Feng Ru was a native son of Enping, a region long known for producing emigrants who carried dreams far beyond its rice fields and riverbanks. Like many others from Guangdong’s Siyi region, Feng Ru left as a child for the promise of a better life in America. But unlike most, he returned—bringing with him blueprints, engines, and a vision of China with wings.

Known as “China’s First Aviator” and “Father of Chinese Flight,” Feng Ru built the country’s first aircraft and piloted its earliest flights—first over California’s fields, then over Guangdong’s skies. His achievements came not in the service of fame or profit, but as an act of national devotion. He died young, but not before proving that even a boy from rural Enping could challenge gravity, borders, and history itself.

Today, his name endures in Enping’s schools, monuments, and memory—but his story deserves a wider sky.

Humble Beginnings in Enping

Feng Ru was born on January 12, 1884, in Xingwei Village, nestled within what is now Enping’s Niujiang Town, a place typical of rural Guangdong: modest homes, hardworking families, and generations rooted in the land. The son of a poor farming household, Feng Ru’s early life mirrored that of countless children in the Siyi (Four Counties) region, where poverty often pushed the brightest minds abroad.

From a young age, Feng Ru showed a mechanical curiosity that set him apart. At the nearby Liantang Enju Private School, he began his formal education, memorizing the Three Character Classic and Confucian texts—but it was outside the classroom where his talent truly emerged. Using scraps of bamboo and discarded paper, he constructed toy boats and miniature carts, fascinated by the way objects moved through water and air.

At age 10, Feng Ru left Enping, journeying across the Pacific to join relatives in San Francisco. Like many early Enping emigrants, his life abroad began with hardship—working by day, studying by night—but he carried with him something rare: an engineer’s imagination and a patriot’s heart. In the smoke-filled workshops and machine rooms of the American West, Feng Ru found the tools to dream bigger than his village, yet never forgot the homeland that shaped him.

It was in those formative years, forged between Enping’s soil and San Francisco’s steel, that China’s first aviator was born.

Awakening in America: Machinery, Identity, and a New Mission

Arriving in San Francisco in the mid-1890s, Feng Ru joined the growing wave of Siyi immigrants—many from Enping, Taishan, and Kaiping—who sought opportunity amid the clamor of Gold Mountain. He found work through kinship networks, laboring by day and teaching himself English and mechanical theory by night. It was an era when Chinese immigrants faced exclusion, discrimination, and isolation. Yet inside the clang of American machine shops, Feng Ru saw something else: the blueprint of national power.

To him, it was clear—“A nation’s wealth and strength comes from industrial prowess.” As the Wright brothers’ 1903 flight redefined the boundaries of human movement, Feng Ru felt not envy but urgency. The Russo-Japanese War underscored what machinery could mean on the battlefield. China, then fractured and technologically backward, needed more than just reform. It needed engineers.

By 1906, Feng Ru had become a skilled mechanic and machinist, inventing small-scale electric generators, pumps, and pile drivers. But his ambition had evolved. Machines alone were not enough. “If I cannot build a plane for China, I would rather die trying,” he once declared. That wasn’t youthful arrogance—it was a solemn vow.

In a rented 80-square-foot workshop on Oakland’s East Ninth Street, supported by fellow Chinese immigrants including young men from the Five Counties, Feng Ru began what no one else had dared: building a functioning aircraft, from scratch, for China.

This was not just invention—it was resistance, diaspora solidarity, and national redemption wrapped into one.

The Birth of Chinese Aviation in Oakland

In 1907, Feng Ru formally launched a bold project that would etch his name into history. With the help of young Chinese immigrants from the Five Counties (Wuyi) region—including supporters like Huang Qi, Zhang Nan, and Tan Yaoneng—he established a tiny workshop in Oakland, naming it the Guangzhou Manufacturing Factory. Its mission was audacious: to design, build, and fly a manned aircraft, long before China even had an air force.

The workshop was little more than a shed—just 80 square feet—but it was filled with energy, tools, and conviction. Backed by 1,000 silver dollars of community funding, this modest space became the birthplace of Chinese aviation.

In September 1909, after months of sleepless nights and failed prototypes, Feng Ru wheeled his creation onto an open field in Oakland’s Piedmont Highlands. Before a stunned crowd, the machine lifted off the ground and flew—briefly, but unmistakably. China’s aviation age had begun.

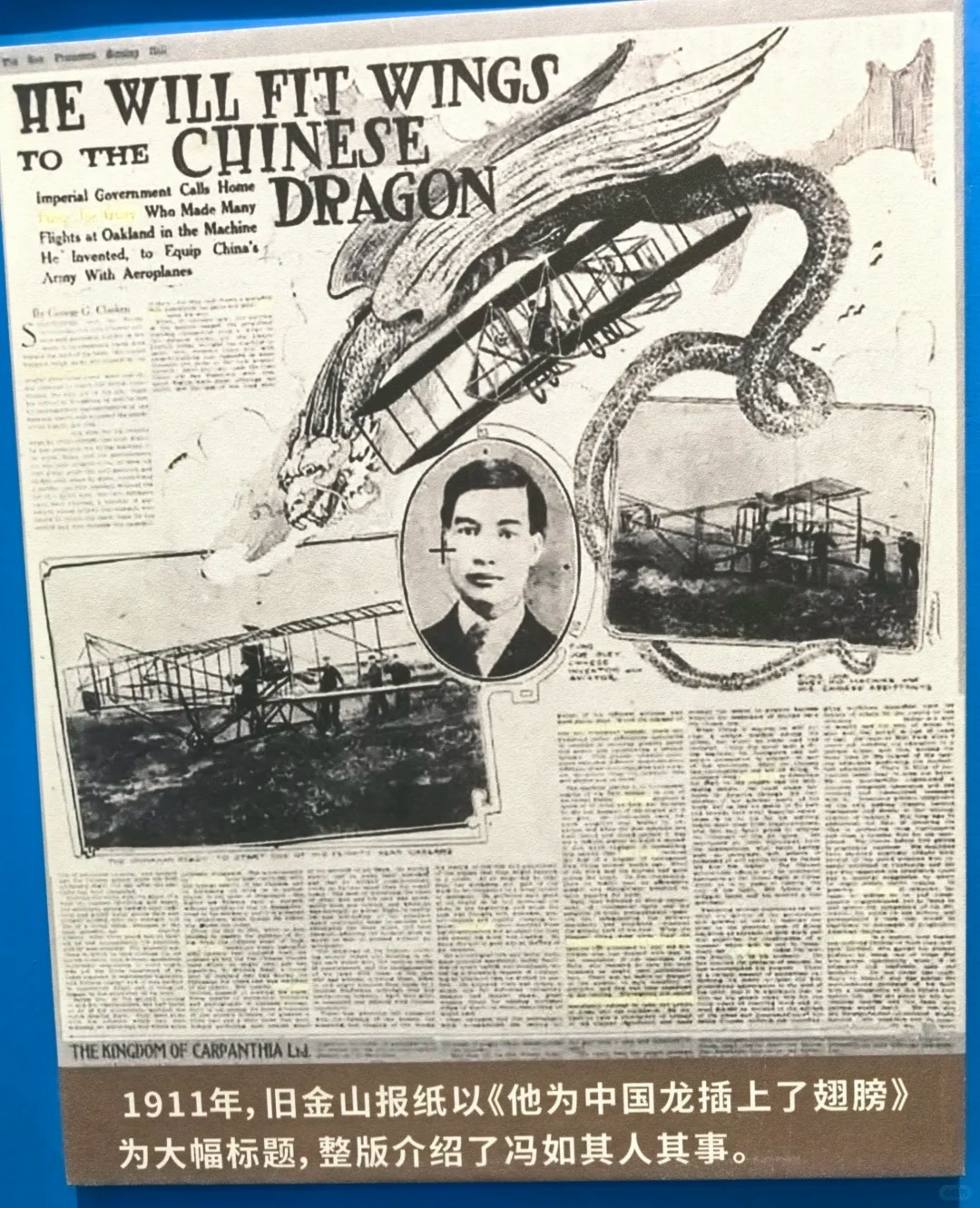

American newspapers quickly took notice. Headlines like “In Aviation, a Chinese Man Surpasses the White Man” and “Feng Ru Flies His Own Plane Over California” stunned readers. In an age when Chinese immigrants were seen as second-class citizens, Feng Ru’s achievement was revolutionary—not just for flight, but for dignity.

The success inspired further investment. By 1910, his team restructured into the Guangdong Manufacturing Company, attracting over 60 investors from the overseas Chinese community. Feng Ru was named Chief Engineer, and new designs soon followed—each one stronger, more ambitious, and more deeply rooted in his unwavering belief: aviation would save China.

Returning to China: A Nation in Turmoil

By 1911, Feng Ru had accomplished what no Chinese before him had: designing, building, and flying functional aircraft in the West. But his achievements were never for personal glory—they were always meant for China. With revolution on the horizon, he packed up two airplanes, manufacturing equipment, and a lifetime of learning, and returned home with a singular goal: to serve the homeland through aviation.

On February 22, 1911, Feng Ru and three trusted colleagues—Zhu Zhuquan, Zhu Zhaohuai, and Situ Bi (from nearby Kaiping)—landed in Hong Kong, then continued to Guangzhou. His timing, however, was difficult. The Qing Dynasty, wary of unrest, placed him under surveillance, suspecting ties to revolutionary factions. His manufacturing plans were suspended, his aircraft damaged in transport, and his movements restricted.

Everything changed with the Wuchang Uprising in October 1911, which sparked the Xinhai Revolution. Soon after, Guangdong declared independence from the Qing, and the provincial military government recognized Feng Ru’s unique value. He was appointed Chief of Aviation for the revolutionary army, tasked with building aircraft in support of the fledgling Republic of China.

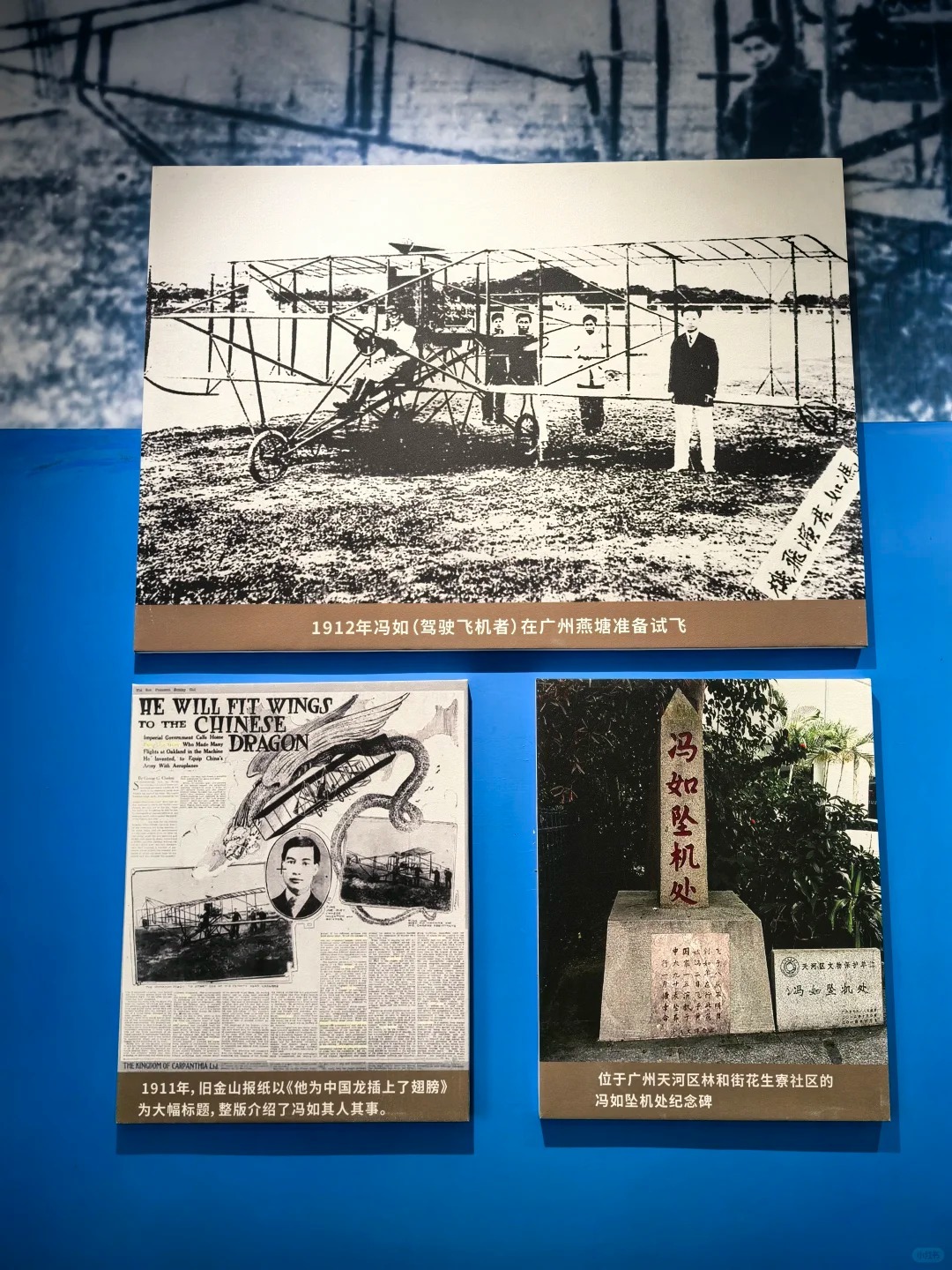

In a converted military facility at Yantang, Feng Ru led the construction of China’s first domestically built aircraft—using bamboo, cloth, wood, and parts he had brought from the United States. By March 1912, the plane was complete, a symbol of industrial modernity crafted under revolutionary urgency.

For the first public flight, Feng Ru chose Taishan—and not by chance. Taishan was known as the cradle of overseas Chinese, home to thousands who had left for Gold Mountain and sent back both money and revolutionary ideas. Many of the early funders of Feng’s aviation efforts in Oakland were Taishanese themselves. Holding the demonstration in Taishan’s Chengnan Field in April 1912, before a crowd of over 2,000, was not just a technical display—it was a tribute to the diaspora’s enduring support for China’s transformation.

That flight was the first time a Chinese person piloted a Chinese-made plane over Chinese soil. And it happened not in Beijing or Shanghai—but in a city where homeland and overseas dreams had always intertwined.

Final Flights and a Martyr’s End

Buoyed by the success of his demonstration in Taishan, Feng Ru pressed forward with renewed urgency. Backed by the Guangdong military government, he transformed the Yantang workshop into the Guangzhou Aircraft Manufacturing Plant—China’s first civil aviation factory. In this modest facility, history was taking shape. Using his knowledge from America and local ingenuity, Feng worked tirelessly to improve the aircraft’s design and performance.

But he understood that engineering alone wasn’t enough. Feng Ru believed aviation had to capture the imagination of the people. With the government’s blessing, he scheduled another public demonstration—this time in Guangzhou’s Yantang Parade Ground, the heart of the provincial capital.

On August 25, 1912, thousands gathered, filling streets, rooftops, and alleyways. Dressed in a flight cap, goggles, and tall leather boots, Feng Ru addressed the crowd:

“For China to become strong, we must master the skies, just as we have the seas.”

He soared into the air to thunderous applause, climbing to 120 feet, then gliding smoothly over 5 miles of countryside. But as he attempted a final ascent, tragedy struck. The aircraft, nose lifted too steeply, stalled mid-air and plunged into a bamboo grove behind the military barracks. The crowd fell silent. Feng Ru was critically injured.

Even as he lay dying, Feng Ru summoned his assistants to his bedside, explaining the cause of the crash, urging them to correct the design—and continue the mission.

He was just 29 years old.

The Guangdong military government, moved by his sacrifice, held a public funeral. His body was laid to rest at Huanghuagang, among the Seventy-Two Martyrs of 1911, a rare honor for someone who died not by the sword, but by the sky.

Feng Ru had flown not just a plane, but a message: modernity and patriotism could—and must—coexist. He died proving it.

Legacy in Enping and Beyond

Though Feng Ru’s life was cut short, his legacy has never faded—especially in his native Enping, where his memory is deeply enshrined in the city’s cultural landscape.

In 1985, the Enping County Government erected the Feng Ru Memorial Hall atop Aofeng Mountain, overlooking the town that once sent a poor boy across the Pacific. His ancestral home in Xingwei Village was later designated a protected heritage site, preserved not just as a historical structure, but as a symbol of what one life of purpose can mean for a people.

Educational institutions such as the Feng Ru Memorial Middle School, along with the Feng Ru Pavilion and Feng Ru Memorial Tower, now bear his name—reminders to future generations that innovation, patriotism, and sacrifice are not abstract ideals, but living history rooted in their own soil.

Outside Enping, his story echoes wherever overseas Chinese communities gather to reflect on their shared past. In San Francisco and Oakland, where his journey began, his name surfaces in Chinese American archives as a source of diasporic pride. In Guangzhou, he remains enshrined alongside revolutionary heroes. And in China’s modern aerospace sector, Feng Ru is often cited as a pioneer whose vision predates jet engines and launchpads, but whose values still lift the nation.

More than a century later, Feng Ru’s story still resonates. He was an immigrant who never forgot his homeland, a mechanic who dreamed beyond borders, and a patriot who turned flight into a form of resistance.

A Sky Worth Remembering

Feng Ru lived only twenty-nine years, but in that brief arc he spanned worlds—Enping and Oakland, poverty and invention, revolution and flight. He represents a generation of overseas Chinese who did not simply seek fortune abroad, but sought the means to uplift the homeland through skill, sacrifice, and vision.

Today, China is an aerospace power. But long before satellites and stealth jets, there was a boy from Xingwei Village who built a plane out of bamboo and cloth, and aimed it at the future. Feng Ru did not live to see that future, but he helped shape it.

In remembering him, we honor more than just the Father of Chinese Aviation. We remember that progress is often born far from the capital, in quiet villages and crowded workshops, among those who dare to believe their wings might carry a nation.

From Enping’s fields to Guangzhou’s skies, Feng Ru’s legacy still flies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Feng Ru

Feng Ru (1884–1912) was a Chinese-American aviation pioneer from Enping, Guangdong. He is widely regarded as the father of Chinese aviation, having built and flown China’s first aircraft and founded its earliest aviation manufacturing efforts.

Feng Ru built and successfully flew a self-designed powered aircraft in Oakland, California in 1909—just six years after the Wright brothers. He later returned to China, founded the country’s first aircraft factory in Guangzhou, and helped organize one of its earliest air forces during the 1911 revolution.

Feng Ru was inspired by the Wright brothers’ success in 1903. Though he worked independently, he followed in their footsteps and became the first Chinese person to build and pilot an aircraft. American newspapers once called him “the Chinese Wright Brother.”

Feng Ru was born in Xingwei Village, Niujiang Town, in Enping County, Guangdong Province. His hometown remains proud of his legacy, with memorials, schools, and museums commemorating his contributions.

Feng Ru died tragically during a public flight demonstration in Guangzhou in 1912 at the age of 29. His aircraft lost balance mid-air and crashed. He was posthumously honored and buried near the Huanghuagang Martyrs, recognized as a national hero.

Feng Ru represents the early fusion of overseas Chinese innovation and patriotic return. His legacy stands as a symbol of technological vision, national devotion, and the important role of diaspora in modern China's development.

Yes. There is a Feng Ru Memorial Hall in Enping, a crash site monument in Guangzhou’s Tianhe District, and multiple schools and landmarks named in his honor. His story is also featured in aviation museums and educational exhibits.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.