The Wuyi Diaspora: A Tale of Clans, Brotherhoods, and Survival

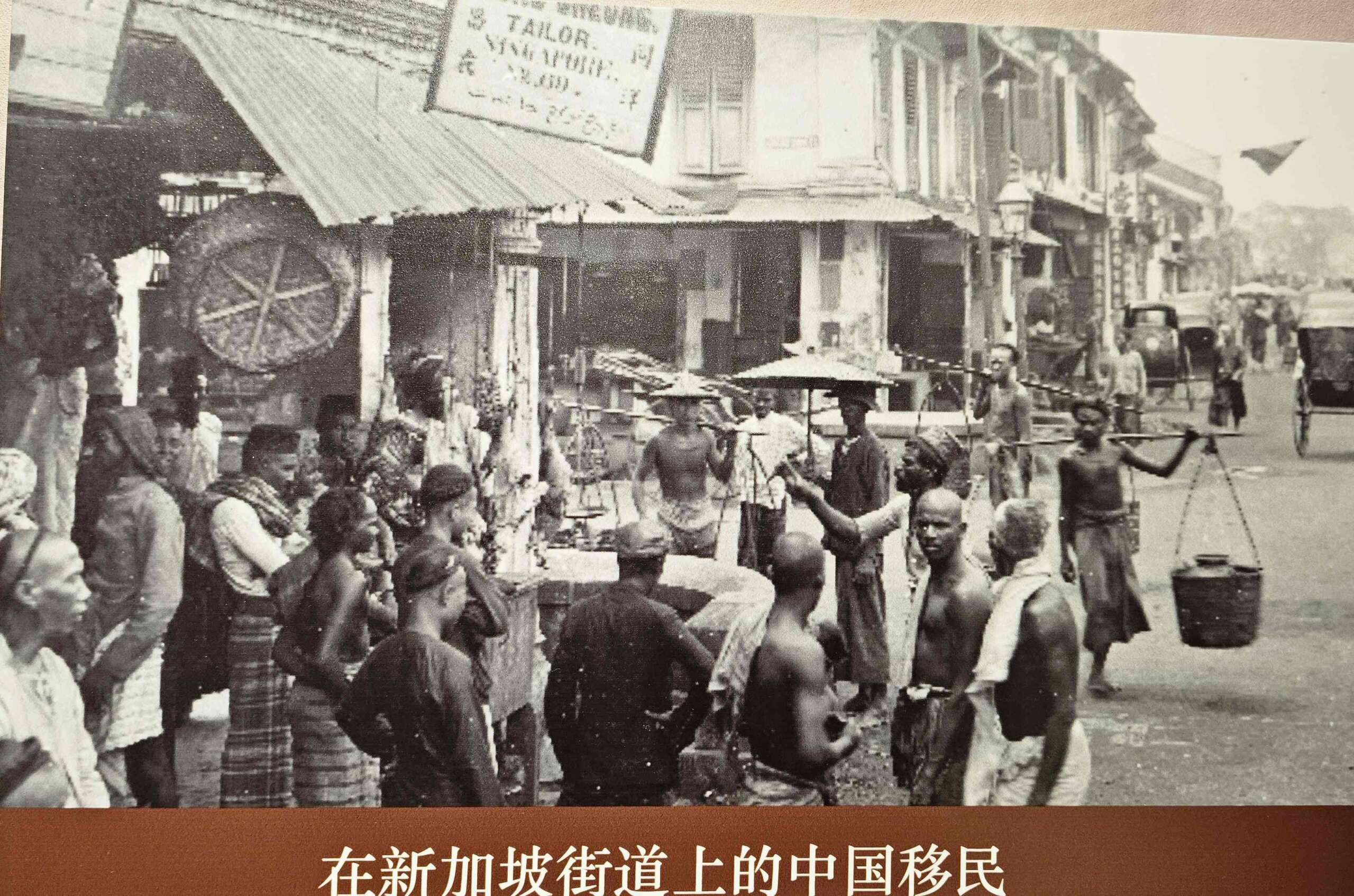

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Wuyi diaspora emerged as one of history’s most remarkable migration stories. Originating from the rural counties of the Wuyi region—such as Taishan in Guangdong Province—tens of thousands of Chinese men embarked on perilous journeys abroad. Driven by economic hardship, colonial labor demands, and the chaos following the Opium Wars, these migrants sought opportunities overseas but often encountered hardship instead. At the heart of their story were intricate social systems they carried with them: clan-based kinship networks and sworn brotherhoods organized through secret societies. These forces shaped the survival, resilience, and conflicts of the Wuyi diaspora communities worldwide.

Setting Sail: Why They Left

Imagine living in the 1880s as a young farmer from Taishan. Your village struggles under failing crops, rising taxes, and an economy destabilized by foreign powers. You hear whispers of work abroad—in Malaya’s tin mines, Canada’s railroads, or Peru’s guano fields. But leaving wasn’t simple. For many migrants, it meant relying on family ties—clan associations that pooled resources to sponsor their passage—or turning to shadowy groups like secret societies if no such connections existed.

The numbers highlight the scale of the Wuyi diaspora : by the late 19th century, over 80% of Chinese immigrants to North America hailed from this region. In 1884 alone, 5,056 laborers left Hong Kong for Canadian railroads, with over 1,150 originating from Taishan. Yet, these journeys came at great cost. Mortality rates were staggering; one Panama railway station earned the grim nickname Mata Chin (“Dead Chinese”). Despite the risks, desperation drove them forward. Once abroad, whether in bustling Chinatowns or remote mining camps, their lives were deeply influenced by the interplay between clans and sworn brotherhoods—a defining feature of the Wuyi diaspora .

Clan Loyalties: Blood Ties Across Oceans

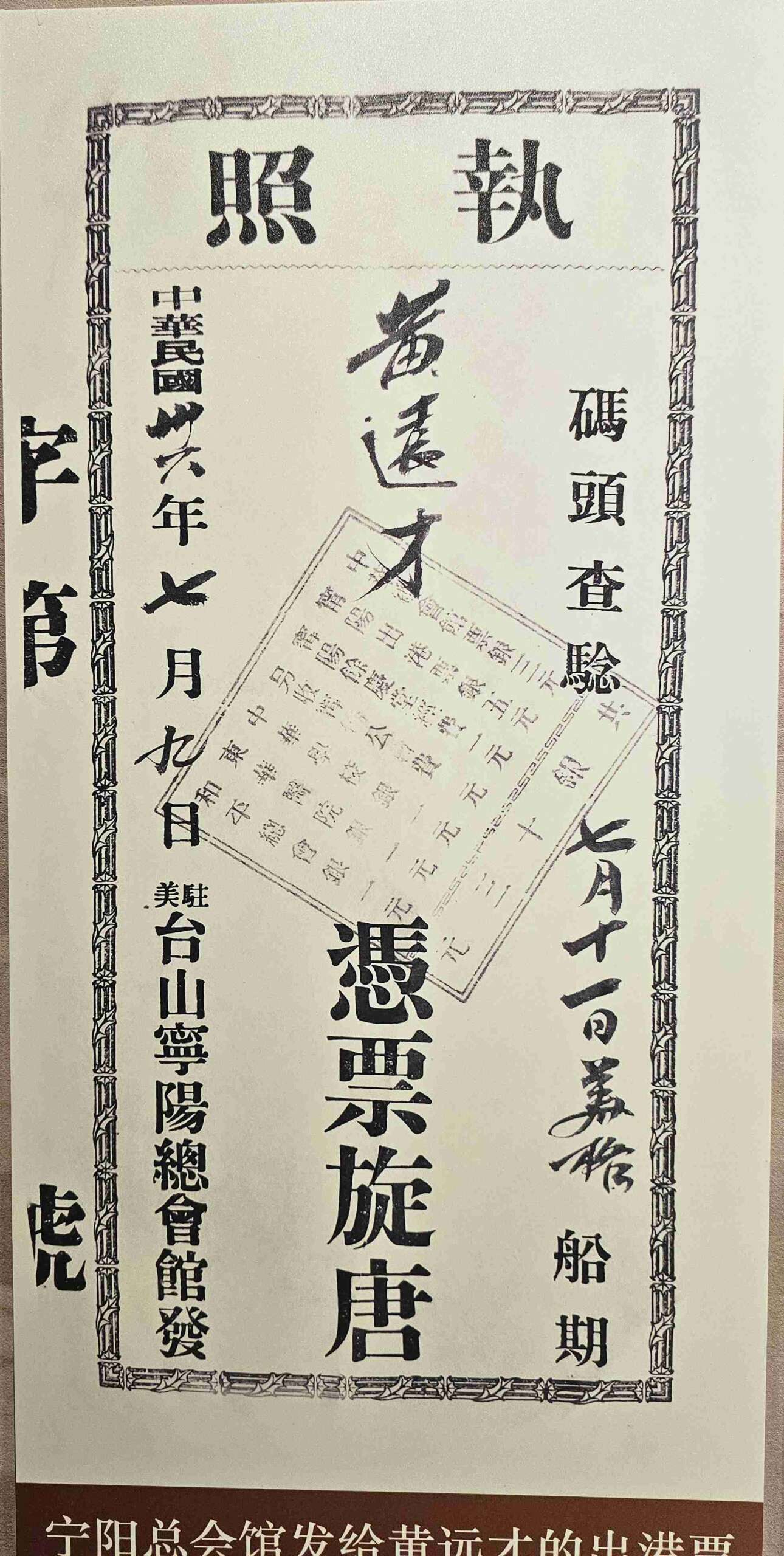

For those fortunate enough to belong to strong clan networks, life overseas was less daunting. Imagine arriving in San Francisco or Singapore and being greeted by relatives who offered shelter, employment, and financial support until you became self-sufficient. This was the power of clan associations like the Ningyang Huiguan (宁阳会馆) in San Francisco, which helped newcomers settle into their new homes.

Clans operated almost like mini-governments within Wuyi diaspora communities. They controlled everything from remittance networks (courtesy of trusted couriers called shuike , or water carriers) to entire industries. For example, Taishanese Chens dominated America’s laundry trades, while Kaiping Lias controlled vegetable farming in Australia’s Northern Territory. New arrivals received housing, jobs, and loans exclusively from clan elders—a system meticulously documented in archives like those of San Francisco’s Six Companies.

However, clans had limitations. Their strict adherence to bloodlines excluded landless laborers, non-kin migrants, and others without connections. This exclusion pushed marginalized individuals toward alternative forms of support, leading to the rise of sworn brotherhoods within the Wuyi diaspora .

Sworn Brotherhoods: Shadows of Solidarity

If clans were the pillars of traditional society, sworn brotherhoods were its shadows. Groups like the Triads (天地会) and Yi Xing Hui (义兴会) emerged as both protectors and challengers to established power structures. Bound not by blood but by oaths, these organizations created tight-knit collectives offering mutual aid, legal defense, and economic opportunities.

Consider the plight of Taishanese migrants working in Peru’s brutal guano mines. When colonial overseers exploited them mercilessly, secret societies stepped in to organize strikes and escape networks. In Southeast Asia, brotherhoods brokered truces during violent clan feuds and facilitated business partnerships in mining districts. However, they also engaged in illicit activities—from smuggling opium to sabotaging clan-controlled industries—that painted them as criminals in the eyes of colonial authorities.

One fascinating aspect involves the “water carriers” (巡城马 ), couriers who transported letters, money, and goods across vast distances. Many collaborated with secret societies to bypass official channels monopolized by clans, enabling survival for marginalized members of the Wuyi diaspora .

Clash of Worlds: Clans vs. Brotherhoods

The tension between clans and sworn brotherhoods was inevitable—and explosive. Clans viewed these secretive organizations as threats to their authority, leading to violent clashes. In 1877 San Francisco, the Chen clan militia fought Triad enforcers over gambling revenue. A decade later in Singapore, the Lee Association banned members from joining Hung Men societies, fearing their influence.

These conflicts reached a fever pitch in places like Malaya’s Larut Valley during the 1880s Tin Mining Wars. Secret societies armed Hakka miners against Taishanese clan interests, sparking bloody confrontations that ultimately ended with British intervention crushing both groups’ autonomy. Such episodes underscored the destabilizing potential of sworn brotherhoods while revealing deep divisions within the Wuyi diaspora .

Legacy: Echoes Across Generations

Today, the legacy of these competing systems remains palpable. Modern family associations retain clan hierarchies but incorporate initiation rituals derived from sworn brotherhoods. Labor movements in the 20th century adopted secret society organizational tactics while rejecting their criminal elements. Even in architecture, symbols of secret societies persist in diaspora temples, quietly preserving their memory.

Academic debates continue about whether sworn brotherhoods ultimately strengthened or undermined migrant resilience. Were they saviors for the marginalized, or disruptors of social order? Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between. What’s undeniable is that the interplay between clans and brotherhoods created lasting patterns of social organization that continue to shape Wuyi diaspora communities worldwide.

A Story of Complexity and Resilience

The Wuyi diaspora wasn’t just a tale of migration—it was a saga of identity, power, and adaptation. Through clans, migrants found structure and solidarity rooted in shared ancestry. Through sworn brotherhoods, they forged bonds based on necessity and survival. Together, these forces wove a rich tapestry of resilience, conflict, and cultural memory that endures to this day.

So next time you walk through a Chinatown, take a moment to consider the hidden histories behind its streets. Beneath the bustling markets and ornate temples lie echoes of a distant past—a past where blood ties and oaths of brotherhood shaped the lives of countless members of the Wuyi diaspora , each striving to carve out a better future against all odds.

FAQ: Understanding the Wuyi Diaspora

The Wuyi diaspora refers to the mass migration of people from the Wuyi region in southern China—particularly counties like Taishan in Guangdong Province—during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Driven by economic hardship and colonial labor demands, these migrants traveled to places like North America, Southeast Asia, and South America, forming vibrant overseas communities shaped by clan networks and sworn brotherhoods.

Migrants from the Wuyi diaspora left due to a combination of factors, including crop failures, rising taxes, and economic instability caused by foreign intervention after the Opium Wars. Many sought work abroad in industries like railroads, mining, and agriculture, hoping for better opportunities despite the risks involved.

Clans played a crucial role in supporting members of the Wuyi diaspora overseas. Clan associations, such as the Ningyang Huiguan, provided housing, jobs, and financial assistance to newcomers. These organizations operated almost like mini-governments, controlling industries and remittance networks while fostering solidarity among kinship groups.

Sworn brotherhoods, such as the Triads and Yi Xing Hui, offered an alternative support system for those excluded from clan networks. Members swore oaths of loyalty rather than relying on blood ties. While they provided mutual aid and protection, these groups also engaged in illicit activities, leading to tensions with clans and colonial authorities.

Conflicts between clans and sworn brotherhoods were common within the Wuyi diaspora. Clans saw brotherhoods as threats to their authority, resulting in violent clashes over resources and influence. For example, disputes erupted in places like San Francisco and Malaya’s Larut Valley, where British intervention eventually curtailed both groups’ autonomy.

Members of the Wuyi diaspora made significant contributions to global economies through hard labor and entrepreneurship. They dominated industries such as laundry trades in America, vegetable farming in Australia, and tin mining in Southeast Asia. Their efforts not only supported local economies but also facilitated cross-border remittances back to their families in China.

The legacy of the Wuyi diaspora endures in modern Chinese communities worldwide. Family associations still incorporate elements of both clan hierarchies and sworn brotherhood traditions. Additionally, symbols of secret societies can be found in diaspora temples, preserving their historical memory. The interplay between these systems continues to shape social organization within Chinese diaspora communities.

The Wuyi diaspora exemplifies universal themes of migration, including resilience, adaptation, and identity formation. It highlights how migrants navigate challenges through communal structures like clans and brotherhoods, creating enduring cultural legacies that transcend borders.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.