The Spirit of Lingnan: What It Means to Come from the South

For many, Lingnan is a region—lush, southern, coastal—stretching beyond the Nanling Mountains where rivers meet the sea and dialects shift with the wind. But to those whose roots lie there, Lingnan is not just geography. It is temperament. It is inheritance. It is a way to live.

Cut off from the imperial heartland by mountains yet open to the world through trade and migration, Lingnan culture evolved in its own current. It prized use over form, loyalty over display, and independence of mind over conformity of voice. Its values weren’t built in palaces or memorized for exams. They were lived—in homes, in fields, and on battlefields.

And one of those battlefields, hidden in the folds of Guangdong’s coast, would define the soul of Lingnan for centuries to come.

Yamen: Where a Dynasty Fell and a Moral Code Rose

In the spring of 1279, the Southern Song court made its final stand against the Mongols in the waters near Yamen, a fishing port near present-day Jiangmen. Onboard the last imperial vessel, the boy-emperor Zhao Bing, just seven years old, clutched his court robes while his chancellor Lu Xiufu prepared for the unthinkable.

As Mongol warships closed in, and with the tide of history already turned, Lu took the emperor in his arms and leapt into the sea.

It was not a strategy. It was a statement: that there are moments in history when death is not defeat, and survival is not victory.

That plunge into the water marked the end of the Song dynasty, but in Lingnan memory, it marked something even greater: the rise of a cultural instinct—to refuse dishonor, even at the cost of life. This was not blind loyalty, but a decision that fused moral clarity with final action.

Temples were built, poems were composed, and for generations, families in Xinhui and beyond would teach the tale of Yamen—not as a tragedy, but as a touchstone. To be from Lingnan was to understand that moment in your bones.

You do what is right—even when history says it doesn’t matter.

What Are Lingnan Values?

To define Lingnan values, you must first understand what the region is not.

It is not the imperial north, where scholars wrote for emperors and Confucianism calcified into ritual. Nor is it the merchant-driven Jiangnan, where success often meant accommodation. Lingnan—separated by mountains, yet brushed by ocean winds—grew into something else entirely: a culture of resilience, shaped by hardship, isolation, and the ever-present need to adapt without losing one’s soul.

It is a culture born of borderlands—where Han Chinese mixed with indigenous peoples, where Buddhism met folk belief, and where Confucian classics were read beside fields rather than palace gates.

Out of this history came a distinct set of values:

Loyalty with Judgment

From Yamen to modern exile, Lingnan loyalty is never blind. It is fierce, but always tempered by personal conscience. When Lu Xiufu drowned with the emperor, he did so not because the system demanded it, but because his own moral compass left no other choice. That’s the essence: you stay loyal to what’s right, not just what’s traditional.

This is why figures like Chen Yuan, centuries later, could refuse to cooperate with occupying forces during World War II. He had no weapons, no army—only silence. Yet for eight years, he never stepped outside Fu Jen University in Beiping, resisting by doing the one thing he could still control: staying true to his ethics.

Usefulness Over Ornament

To a Lingnan mind, learning that doesn’t serve life is a kind of fraud. Education is sacred, but only when it touches the real: family, land, action, character. This is why Chen Xianzhang could write poetry with a bundle of wild grass and call it art—not because it looked refined, but because it was true to the moment.

His life as a “half farmer, half scholar” wasn’t a contradiction—it was a statement. You till the soil and you till the soul. You speak simply so your neighbor understands you. This is the useful Confucianism of Lingnan: ethical, grounded, alive.

Adaptability Without Losing Self

History forced Lingnan to adapt. Floods, invasions, epidemics, migration—each generation had to bend or break. And yet, through it all, there is an uncanny continuity: a rootedness. A sense that even when circumstances change, there are lines one doesn’t cross.

Liang Qichao, born in a humble village, grew into a reformer, journalist, political theorist—and yet never forgot his rural beginnings. His writings are full of moral struggle and reinvention, but always anchored in core values: justice, conscience, renewal. He famously wrote:

“I do not fear challenging the self of yesterday with the self of today.”

That’s Lingnan transformation—bold, self-critical, never rootless.

Moral Action Over Public Performance

In Lingnan tradition, righteousness is measured by what you do when no one is looking. Grandstanding is suspect. The greatest figures often lived modestly, resisted quietly, or died anonymously. It’s not that Lingnan discourages ambition—it simply holds character above all.

In village genealogies, you’ll often find more space devoted to a great-grandfather who defended the clan during a famine or rebuilt an ancestral shrine after war than to one who passed the civil exam. Survival with honor meant more than success without it.

Three Lives, One Spirit: Lingnan Values in Action

The ideals of Lingnan are not found in abstract theory—they live in decisions, habits, and the moral instincts passed down across generations. While history records great names, Lingnan culture has never been about fame. It is about how one lives.

Still, a few lives shine not because they sought the spotlight, but because they quietly carried the region’s spirit forward. Three sons of the Wuyi Region—Chen Xianzhang, Liang Qichao, and Chen Yuan—each reveal a facet of Lingnan’s enduring character.

Chen Xianzhang: Nature as Teacher, Simplicity as Strength

A poet, philosopher, and farmer, Chen Xianzhang walked the hills of Guifeng in Xinhui not to escape society, but to better understand it. His “grass dragon brush,” fashioned from cogongrass on a mountaintop, is more than a folk tale—it is a symbol of usefulness over ornament.

In his world, you did not need silk robes or rare ink to write truth. You needed attentiveness to nature and commitment to clarity. He taught that learning without application is noise, and that true wisdom must speak plainly to ordinary people. This was Lingnan pragmatism, expressed in verse and fieldwork.

Liang Qichao: Reform Rooted in Conscience

Born in a farming village in Xinhui, Liang Qichao rose to become one of the most influential thinkers of modern China. But his brilliance was shaped less by exams than by family—by his grandfather’s quiet discipline and his father’s moral expectations. He was taught that righteousness must be practiced, not preached.

When he later called for a reformed China led by “new citizens,” it was not a Western idea—it was a Lingnan idea, filtered through his Southern upbringing: question tradition, adapt boldly, but never forget your moral core.

He once asked, “Do you really see yourself as just an ordinary person?” That wasn’t arrogance—it was the voice of a tradition that expects every person to carry the weight of justice, however small their station.

Chen Yuan: Resistance Without Drama

During the Japanese occupation of Beijing, Chen Yuan—a mild-mannered historian from Xinhui—refused to collaborate. For eight years, he remained on the grounds of Fu Jen University, writing history as an act of resistance. No speeches. No slogans. Just silence, endurance, and work.

This was Lingnan loyalty with judgment. Not loud nationalism, but quiet refusal. Not martyrdom for spectacle, but moral clarity lived in isolation.

When the war ended, a visitor found Chen pale but composed. He had not seen the outside world in nearly a decade. But he had kept faith with himself, and with the tradition that shaped him.

Lingnan, Still: A Living Inheritance

Today, Lingnan exists not only in geography but in memory—in the language we speak with elders, in the decisions we make under pressure, in the quiet way we hold fast to what matters.

You don’t need to have stood in Yamen to feel its echo. You don’t need to be a philosopher to understand Chen Xianzhang, or a reformer to relate to Liang Qichao. What they carried forward—honor, usefulness, conscience, steadiness—is not rarefied. It is found in everyday choices.

For those in the diaspora, tracing lineage back to the Wuyi region, these values are more than cultural artifacts. They are the inheritance that crosses oceans:

- The family stories that emphasize effort over appearance

- The instinct to serve without boasting

- The refusal to bend, even when the world says to

In a time when culture can feel either commodified or distant, Lingnan values offer something rooted, personal, and quietly powerful.

Not a brand. Not a trend.

A way to live.

“Mountains and rivers divide us, but the spirit remains. When we remember, we return.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Lingnan values refer to the moral and cultural ethos developed in the southern region of China, especially in Guangdong and Guangxi. Rooted in history, they emphasize practical wisdom, moral integrity, loyalty with judgment, adaptability, and a deep respect for learning that serves life rather than ceremony or status.

Lingnan literally means “south of the Nanling Mountains.” It includes modern-day Guangdong, Guangxi, and parts of Hainan. Its culture stands apart due to its geographic separation, intercultural blending, and a long history of resistance, trade, migration, and local intellectual traditions.

In 1279, during the Battle of Yamen, the Southern Song dynasty made its final stand against the Mongol-led Yuan forces. Minister Lu Xiufu, carrying the young Emperor Zhao Bing, leapt into the sea rather than surrender. This act of sacrifice has since become a symbol of Lingnan loyalty and moral courage.

Three major figures illustrate different facets of Lingnan culture:

- Chen Xianzhang (Chen Baisha): A philosopher-poet who embodied natural simplicity and learning rooted in life.

- Liang Qichao: A reformist thinker whose southern upbringing shaped his modern political vision.

- Chen Yuan: A historian who upheld moral resistance during wartime through scholarly integrity.

For many overseas Chinese, especially those with roots in southern China, Lingnan values connect them to a legacy of resilience, conscience, and quiet strength. These values offer a way to interpret family traditions, moral choices, and identity through a historical and cultural lens that remains deeply relevant today.

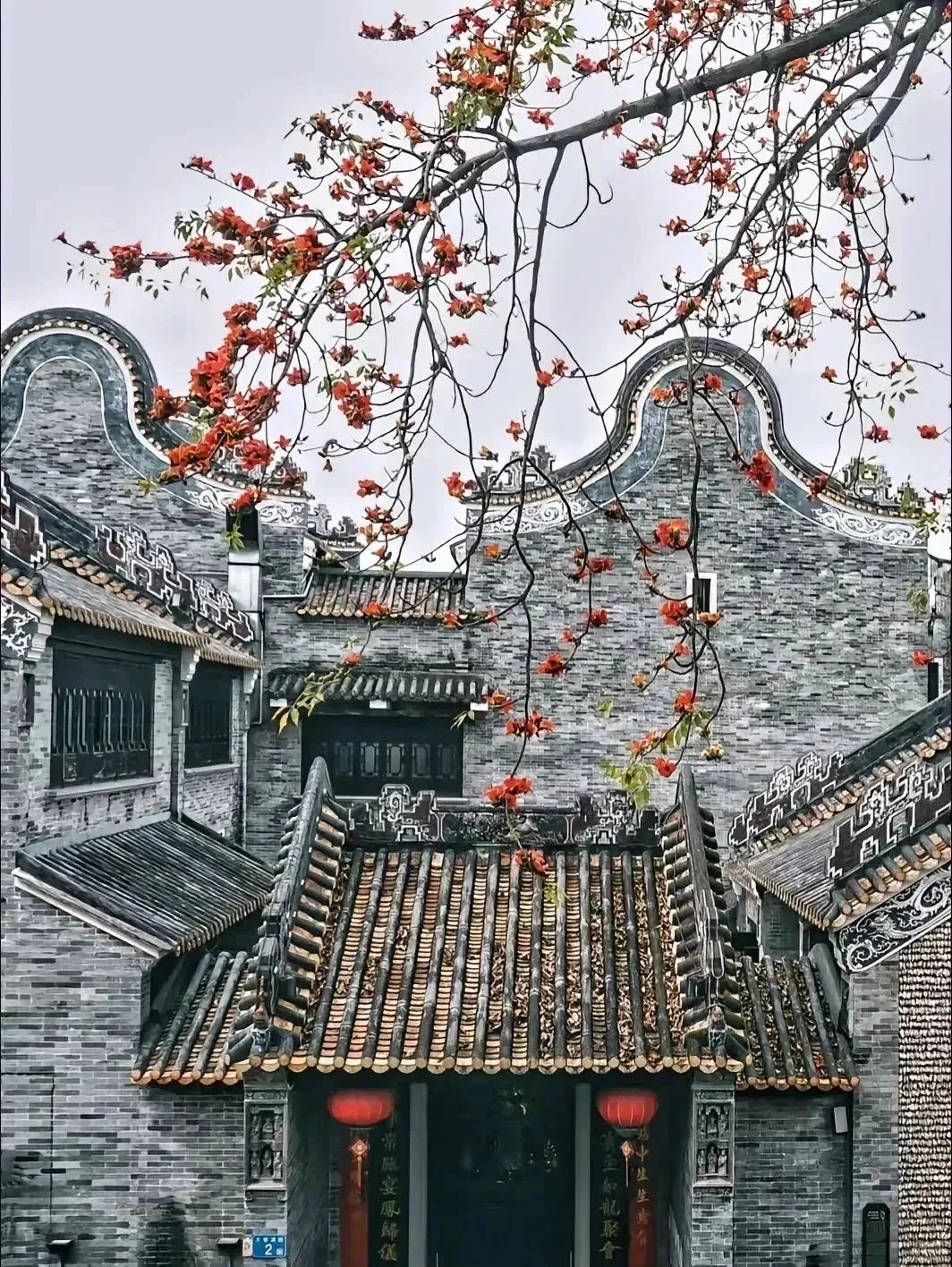

Traditional Lingnan structures, like the wok-ear houses (镬耳屋) and ancestral halls, reflect a focus on function, symbolism, and harmony with nature. Their design supports not only the subtropical climate but also cultural beliefs around protection, prosperity, and social order.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.