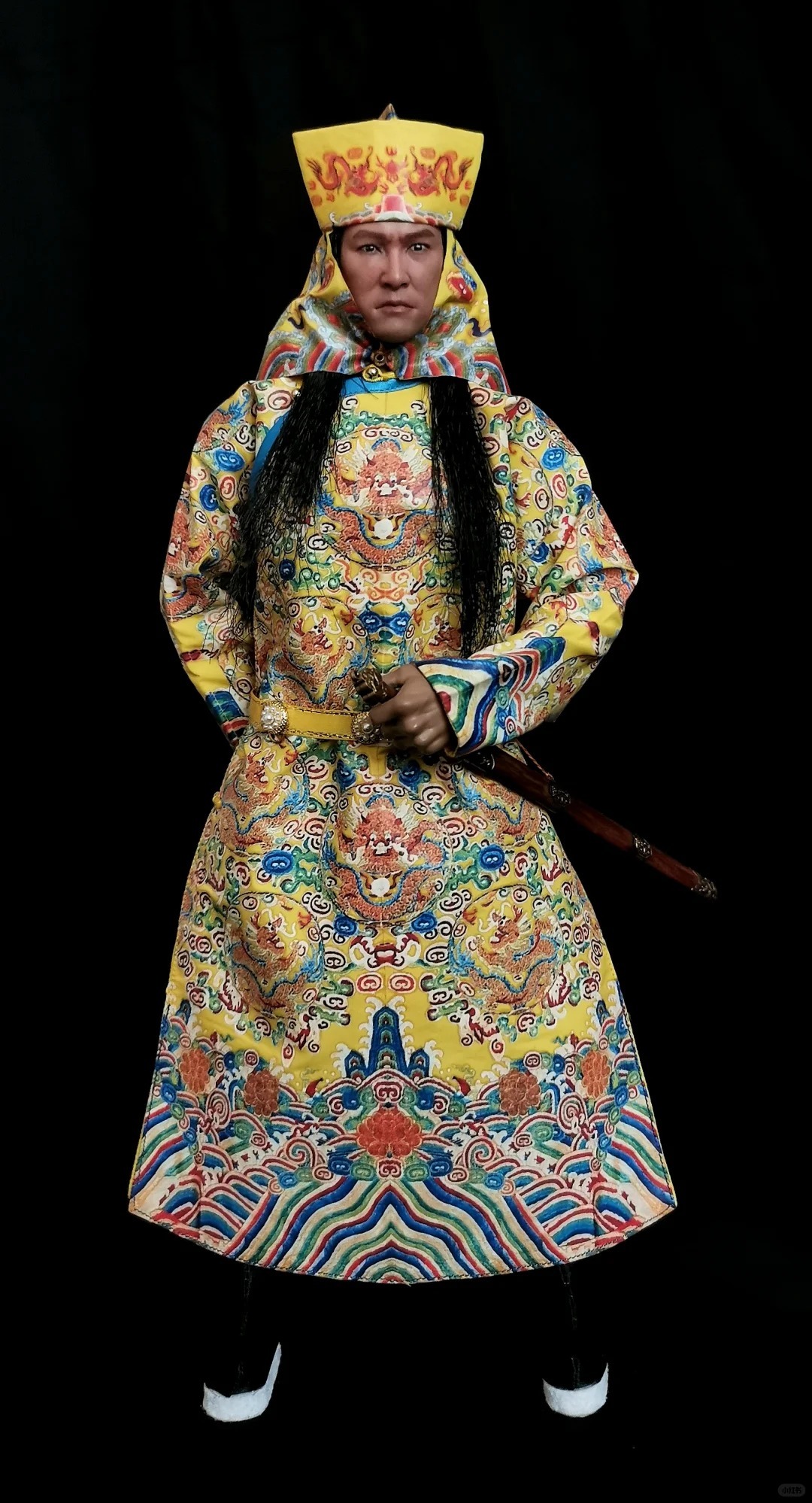

I Am Sun Yet-Sen Founder of Modern China: Awaking the Rebel Part 2

When I was born on November 12, 1866, the Qing Dynasty had just extinguished the last embers of the Taiping Rebellion . The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) was one of the deadliest civil wars in history, led by Hong Xiuquan , a failed scholar who claimed to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ. He sought to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and establish a “Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace,” promising land reform, equality, and an end to corruption. Though the rebellion shook the Qing to its core, it ultimately failed, leaving millions dead and the country further weakened.

Some would later say that from the moment I entered this world, I carried a weight of responsibility—a destiny to challenge the oppressive rule of the Qing, much like Hong Xiuquan had attempted decades earlier.

A Childhood of Poverty and Curiosity

We were tenant farmers, eking out a living on land we rented from landlords. Though we cultivated rice, I rarely tasted white rice as a child. Instead, I subsisted on sweet potatoes and other hardy crops introduced from the Americas—crops that quite literally kept me alive. My childhood was marked by mischief: climbing trees to steal bird eggs, swimming in rivers to catch fish, even riding horses that didn’t belong to me. Once, I fell off one such horse and nearly broke my leg. But perhaps what shaped me most was watching the secret martial arts groups in our village practice their routines. I’d sneak peeks at their drills, then return home to mimic their movements, dreaming of becoming a great warrior who could fight injustice.

When I was seven or eight, an old man named Feng Shuanguan settled in our village. A veteran of the Taiping Rebellion, he often sat beneath the banyan tree in front of his house, regaling children with tales of rebellion—from the uprising at Jintian to the capture of Nanjing. His stories captivated me, planting seeds of revolution in my young mind. One day, teasingly, he said to me, “You look like Hong Xiuquan. When you grow up, why don’t you become another Hong Xiuquan?” To a boy of my age, those words felt like a badge of honor. From then on, my friends called me “Hong Xiuquan,” and I proudly led them in games of war, imagining myself leading armies against tyranny.

If overthrowing the Qing became my life’s mission, its roots were planted in those early days of play and storytelling.

Education and Rebellion

At the age of nine, I finally began attending a private school, where I studied Confucian classics like the Three Character Classic and the Five Classics . But these lessons frustrated me. Our teacher demanded rote memorization without explaining the meaning behind the texts. Dissatisfied, I challenged him constantly, insisting he explain the significance of the words we recited. This earned me frequent punishments—beatings or forced recitations—but also quiet admiration. Behind my back, he told my father, “Sun Dixiang will achieve great things one day.”

Still, formal education ended abruptly for me. After two years, my teacher passed away, and I transferred to another private school. Around this time, my older brother Sun Mei returned from Hawaii, having amassed wealth through farming and trade. He recruited laborers to join him in Hawaii, promising opportunities abroad. Watching villagers clamor to follow him ignited a burning desire within me to see the world beyond Cuiheng.

But my father, haunted by memories of his brothers’ deaths overseas, refused to let me leave. At 65, he feared losing his only remaining son. So, while I watched my brother depart with over a hundred hopeful workers, I stayed behind, seething with frustration. Yet, the fire inside me only grew stronger.

First Glimpse of the World Beyond

Two years later, a British steamship set sail from Macau to Honolulu. Desperate to escape the confines of rural life, I begged my father to let me travel to Hawaii. By then, my brother had established himself as a successful planter with 6,000 acres of farmland and various businesses. My mother, eager to visit her eldest son, agreed to accompany me. Reluctantly, my father relented.

The journey across the ocean filled me with exhilaration. For 20 days, I marveled at the vastness of the sky and sea, feeling as if I’d broken free from the narrow confines of my childhood. Arriving in Hawaii was transformative. It was as though I’d stepped out of a well into a wider world, seeing possibilities I never imagined. My mother, however, struggled to adapt and soon returned home. Meanwhile, I learned that my brother’s success stemmed partly from marrying a local woman, which granted him access to land and resources. His achievements, though impressive, seemed difficult to replicate.

After a brief stay, my brother assigned me to work in his store, handling accounts—a task utterly unappealing to a restless teenager like me. I pleaded with him to allow me to attend school instead. Recognizing the value of education, especially Western knowledge, he enrolled me in Iolani College, a prestigious Anglican missionary school. Tuition cost 150 dollars annually—an enormous sum—but my brother spared no expense for my future.

At Iolani, I encountered subjects and teaching methods unlike anything I’d experienced before. Lessons in politics, natural sciences, and English opened my eyes to new ways of thinking. The disciplined environment and emphasis on critical thought inspired me to dream of reforming China’s outdated education system. Religion, too, left a profound mark. Through Bible studies, I discovered Christianity’s message of equality and love—a stark contrast to the authoritarian hierarchy of traditional Chinese beliefs. Gradually, I embraced these teachings, even going so far as to destroy an ancestral shrine dedicated to Guan Yu, the revered deity of loyalty and righteousness.

This act sparked outrage among Chinese laborers working for my brother. They viewed Guan Yu as a spiritual anchor, akin to Jesus Christ for Christians. Fearing further scandal, my brother cut short my education and sent me back to China in July 1883.

My first taste of Western enlightenment had come to an abrupt end.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.