The Coolie Trade and Early Migration Patterns (1840–1874)

The mid-19th century marked a dark yet transformative period in Chinese migration history, dominated by the global coolie trade (苦力贸易). Tens of thousands of laborers, predominantly from Guangdong’s Taishan, Xinhui, and Enping counties, were swept into this exploitative system. Between 1840 and 1874, over 200,000 Chinese workers were shipped to destinations such as Peru, Cuba, and Southeast Asia under coercive contracts (契约华工). Many fell victim to a brutal practice known as selling piglets (卖猪仔), where deception and kidnapping were rampant.

This mass migration was not an isolated phenomenon—it was driven by intersecting forces. Western colonial powers sought cheap labor after the abolition of slavery, while the Qing Dynasty, weakened by the Opium Wars (1839–1842), could not protect its people. In rural Guangdong, desperate poverty pushed families to take unimaginable risks, fueling the growth of the coolie trade .

The conditions these laborers faced were horrific. In Peru, guano islands and railroads became death traps, with mortality rates exceeding 60%. In Cuba, sugar plantations mirrored the horrors of slavery. Yet, even amid such suffering, these laborers laid the groundwork for vibrant diasporic communities. Their remittances (银信) revitalized their ancestral villages, creating enduring transnational ties.

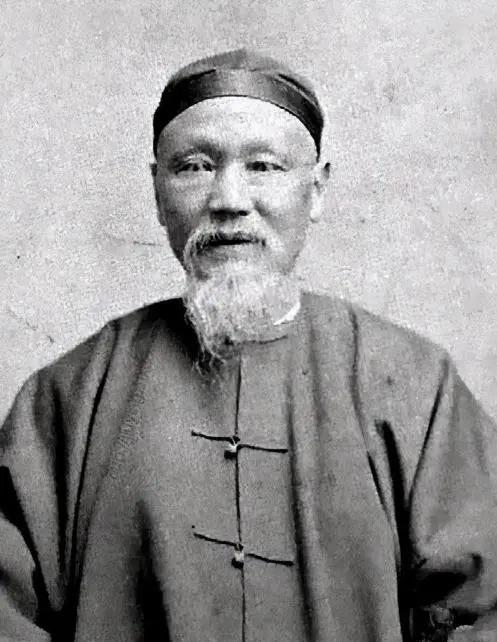

Although the Qing government eventually intervened—most notably through Chen Lanbin (陈兰彬), who led a pivotal 1874 investigation into the abuses faced by Chinese laborers abroad—his efforts were conducted prior to his formal diplomatic role. This investigation exposed systemic exploitation within the coolie trade and pressured foreign powers, such as Spain, to formally end the practice. Survivor accounts, like letters from Taishanese miner Mao Yuguang, and modern discoveries, such as Peruvian auditor Victor Caso Lai tracing his roots, highlight that this history is about more than exploitation—it’s also about resilience, survival, and the creation of transnational identities.

This article explores how the coolie trade reshaped global labor networks and embedded cultural survival strategies—such as clan associations and hybrid cuisines like Chifa—that endure today. By amplifying the voices of Cantonese migrants, often sidelined in Eurocentric narratives, we confront both the trauma of unfree labor and its unintended role in forging connections across borders.

Recruitment and Deception: The Broken Promises of “Gold Mountain”

The journey into the coolie trade didn’t start on ships—it began in the narrow alleys of Guangdong’s market towns. Labor recruiters, or 客头 (kètóu), painted glittering pictures of 金山 (Gām Sāan, or “Gold Mountain”). For poor farmers and fishermen, especially those from drought-stricken Taishan villages, these brokers dangled contracts stamped with foreign seals, promising wages that could lift their families out of debt. What they didn’t realize? They were signing indentured servitude agreements (卖身契) that would bind them for eight grueling years under life-threatening conditions.

Fraudulent advertising was rampant. Brokers flashed stacks of silver dollars and paraded “returned migrants” in fancy Western clothes—often paid actors—to lure recruits. One 1862 broadside promised “$4/month” in Cuba. Sounds enticing, right? Not so fast. The credit-ticket system (赊单工) forced laborers to work off inflated travel costs, trapping them in perpetual bondage. And then there was the infamous “piglet trade,” where men were drugged, beaten, and dragged to Macau’s Barracoons (holding pens). As one Qing official lamented in 1859, “Even dogs are treated better than these ‘pigs’ sold overseas.”

Who were these laborers? Over 90% came from just four counties: Taishan, Xinhui, Enping, and Kaiping. Clan networks funneled kinsmen to specific destinations—for example, Taishanese men often ended up building railroads in Peru. Most were young men (95%), aged 14–30. Literate recruits sometimes forged documents to pass as “cooks” or clerks, skirting bans on skilled labor emigration after 1860.

Here’s where it gets darker. In Havana, Cuban planters openly ignored the 8-hour workday clause in Chinese contracts by presenting a second, hidden contract upon arrival. This one demanded 14-hour days under armed overseers. When laborers protested, agents cited Clause 12: “Disobedience justifies corporal punishment.” This systemic fraud was later exposed by Chen Lanbin’s investigation team in 1874.

Key terms like piglet dens (猪仔馆) and folk rhymes like 卖身契七年痛苦,死后骸骨难回乡—“Seven years of pain under contract; even my bones won’t return home”—capture the desperation and exploitation baked into every level of the coolie trade .

Routes and Conditions: The Floating Hell of the Coolie Trade

The journey from Guangdong’s Pearl River Delta to places like Cuba’s plantations or Peru’s guano pits was nothing short of hellish. Known as the “floating hell” (浮动地狱), these voyages became synonymous with suffering, disease, and death—a grim testament to the brutal realities of the coolie trade .

Imagine this: ships designed for 300 people routinely carried 600 or more men in locked, overcrowded holds, each allotted less than 8 square feet of space. Disease spread like wildfire—cholera, dysentery, and scurvy were rampant. Survivors recounted whippings for refusing rancid food (“We ate rice crawling with maggots”) and shackles for attempted escapes. At least 38 documented mutinies occurred between 1845 and 1872, including the infamous Norway uprising (1857), where Taishanese laborers set their ship ablaze rather than face enslavement in Cuba.

Take the Dolores Ugarte , for example. In 1870, this Peru-bound ship saw a fire outbreak that killed 45% of its passengers. Guards left the coolies to perish in the chaos. Or consider the harrowing voyage of the Kate Hooper . Departing from Hong Kong in October 1857, the ship carried 652 Chinese laborers—coolies who had been deceived into believing they were headed to San Francisco, not Cuba. When the truth emerged four days out of Macao, the laborers revolted, attempting to seize control of the ship by setting fires and breaking up parts of the vessel. The crew responded with brutal force, suppressing the uprising using small arms, suffocation tactics (covering hatches with tarpaulins to cut off air), and severe punishments. Five ringleaders were executed during the voyage—some shot on deck, others thrown overboard and shot mid-sea—as examples to deter further rebellion. Eighteen others were placed in double irons and kept restrained until just before landing in Havana. Despite the crew’s efforts to maintain order, the Kate Hooper signaled distress at one point, prompting assistance from an American vessel, the Flying Childers , which provided reinforcements and additional arms. By the time the ship reached Havana in February 1858, 38 laborers had died, bringing the mortality rate for the voyage to 6%, significantly lower than the average 17% for similar journeys during that period.

Survivors who made it to Havana or Callao faced new horrors. La Trata Amarilla (“Yellow Trade”) auctions stripped them naked and inspected them like livestock before plantation owners bid on their contracts. Immediate branding with numbers awaited those sold to Peruvian guano mines (e.g., “No. 352 – Hacienda San Nicolás”). One survivor, Li Ah Ming from Enping, testified to Qing investigators in 1874: “They pushed us into wooden barracks surrounded by skulls… The air smelled of rotting flesh and saltpeter.”

Labor Systems Abroad: From Sugar Plantations to Railroads

The coolie trade didn’t just shuffle Chinese laborers across oceans—it plugged them into brutal colonial economies where exploitation was the rule, not the exception. Whether it was sugar plantations in Cuba, guano pits in Peru, or railroads in the U.S., these systems shared one thing in common: they extracted every ounce of energy from Chinese bodies while treating them as disposable.

In Cuba, sugar plantations demanded 18-hour days under the scorching Caribbean sun. If you slowed down? Whipped. Too tired to keep going? Still whipped. Mortality rates here hit a staggering 40% between 1860 and 1874. And get this—most contracts were voided upon arrival, leaving workers trapped without legal recourse. Suicide became so common that entire barracks would mourn nightly.

In Peru, the Chincha Islands weren’t just hellish—they were deadly. Workers scaled cliffs carrying heavy baskets filled with ammonia-rich guano under relentless heat. Chemical burns? Check. Collapsing piles burying men alive? Double check. One British consul report coldly noted, “No one dug them out—just dumped more guano on top.”

Even in the U.S., where conditions were marginally better compared to Peru or Cuba, the Sierra Nevada tunnels claimed over 500 lives due to avalanches alone. Paid half what white workers earned ($26–35/month), Chinese laborers still managed to build some of the most dangerous stretches of track. Their legacy? Etched into the very rails that connected America—but largely erased from history books.

Despite the brutality, laborers found ways to resist and survive. Sabotage, like slowing down work (磨洋工) or pretending to be sick, became acts of defiance. Escape networks helped Taishanese form secret brotherhoods in Lima to flee abusive employers. Cultural preservation thrived through clan associations (会馆) and traveling opera troupes that kept traditions alive.

Legacy in language tells part of the story too. The Spanish term chinochamp (from chino + champán, “Chinese foreman”) reflects how Cantonese overseers—often former coolies themselves—became intermediaries between bosses and new arrivals.

Qing Dynasty Responses: Between Neglect and Intervention (1840–1874)

If you think the coolie trade was bad, wait until you hear how the Qing government handled it—or rather, didn’t . Their response was a rollercoaster ride of contradictions: indifference, complicity, and finally, belated humanitarianism.

At first, the Qing shrugged off complaints about the coolie trade . Emigrants? They were seen as abandoning ancestral graves (背祖忘宗)—basically traitors unworthy of protection. Local officials in Guangdong happily collected emigration taxes (人头税) while ignoring desperate petitions like this 1858 letter from Taishan clans: “Our sons are shackled in Havana like cattle!”

Things changed when two high-profile investigations exposed the horrors abroad. In Havana, Cuban planters openly flouted the 8-hour workday clause in Chinese contracts by presenting a second, hidden contract upon arrival. This one demanded 14-hour days under armed overseers. When laborers protested, agents cited Clause 12: “Disobedience justifies corporal punishment.” This systemic fraud was later exposed by Chen Lanbin’s investigation team in 1874.

Even as the Qing condemned Western abuses, they still called returnees “traitors” (汉奸). But after 1874, attitudes shifted. Overseas Chinese began being viewed as sources of remittances and potential allies in anti-Qing revolutions (hello, Sun Yat-sen!). This marked the birth of Haiwai Huaren (“Overseas Chinese”) identity—a transnational phenomenon shaped by both neglect and necessity.

Verdict? The Qing response evolved—but only after tens of thousands had already perished abroad.

Legacy and Memory: Bones Across the Pacific

What happens when trauma becomes lineage? When ink and bone forge an unbreakable connection across generations? That’s the story of the coolie trade’s legacy—a haunting mix of pain, memory, and resilience.

In Taishan’s dusty village archives, fragile envelopes hold letters written in desperation. Take Huang Ah Fu’s 1871 note: “Father, I am in Peru. The mountain eats men. Every month, 30 die in the tunnels… If you receive $8, it means my bones are already white.” These letters served dual purposes: coded warnings to avoid deadly worksites (e.g., “Do not go to Hacienda San Nicolás—no one leaves alive”) and epitaphs used by clans to erect empty graves (衣冠冢).

By the 1890s, clan associations pooled wages to repatriate remains—a sacred duty under Confucianism. Temples like 公益金骨堂 stored thousands of labeled skulls awaiting shipment home. Before burial, remains were boiled with ginger and rice wine to “purify foreign soil.”

Fast forward to 1998. In Heshan, Peruvian-born auditor Victor Caso Lai knelt before a tombstone engraved with his great-grandfather’s contract number (No. 8872). His journey mirrored reverse migration patterns: discovering family letters confirming origins in Guangdong, donating $50,000 to rebuild an ancestral hall destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, and grappling with an identity crisis. “I thought I was Peruvian until I read Grandfather’s suicide note in Cantonese…”

Today, their legacy endures in tangible ways. Toronto’s Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial Park stands as a tribute to the more than 4,000 workers who lost their lives—many of whom can be traced back to Taishan clans. It serves as a lasting acknowledgment of the Chinese community’s vital contributions to the construction of the transcontinental railway.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Coolie Trade

The coolie trade (苦力贸易) refers to the mid-19th-century system of indentured labor that transported hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers, primarily from Guangdong’s Taishan, Xinhui, and Enping counties, to destinations like Peru, Cuba, and Southeast Asia. These laborers were often deceived or coerced into signing contracts (契约华工) under exploitative conditions, working in industries such as sugar plantations, guano mines, and railroads. The term “coolie” itself reflects the derogatory label given to these laborers, who faced immense hardships and systemic abuse.

The coolie trade emerged due to intersecting global forces:

- Western colonial demand: After the abolition of slavery, colonial powers sought cheap labor to sustain their economies.

- Qing Dynasty weakness: Following the Opium Wars (1839–1842), the Qing government lacked the resources to protect its citizens from exploitation.

- Local poverty: In rural Guangdong, desperate families saw migration as a way to escape extreme poverty, even if it meant risking dangerous journeys abroad.

These factors created a perfect storm for the rise of the coolie trade, which became a lucrative but brutal enterprise.

Recruitment for the coolie trade was rife with deception and coercion:

- False promises: Labor brokers, known as 客头 (kètóu), lured recruits with glittering tales of wealth in “Gold Mountain” (金山), claiming high wages and better lives overseas.

- Fraudulent contracts: Many signed agreements without understanding the harsh realities, including clauses that bound them to years of servitude.

- Violence and kidnapping: Practices like the infamous “piglet trade” (卖猪仔) involved drugging, beating, and forcibly transporting men to holding pens (猪仔馆) before shipping them abroad.

This recruitment process highlights the exploitative nature of the coolie trade and its devastating impact on vulnerable communities.

The voyages of the coolie trade were notoriously referred to as the “floating hell” (浮动地狱). Conditions included:

- Overcrowding: Ships designed for 300 passengers often carried 600 or more laborers, each allotted less than 8 square feet of space.

- Disease outbreaks: Cholera, dysentery, and scurvy spread rapidly in unsanitary conditions.

- Brutal treatment: Laborers faced whippings, shackles, and execution for attempted escapes or rebellion.

- High mortality rates: Voyages had an average mortality rate of 17%, with some ships losing nearly half their passengers.

Examples like the Kate Hooper mutiny underscore the desperation and suffering endured during these journeys.

Coolies worked in various industries, depending on their destination:

- Cuba: Sugar plantations demanded 18-hour days under armed overseers, with mortality rates exceeding 40%.

- Peru: Guano pits exposed workers to toxic ammonia, collapsing cliffs, and chemical burns.

- United States: Chinese laborers built railroads through treacherous terrain, facing avalanches and discrimination despite contributing to major infrastructure projects.

Regardless of location, the coolie trade subjected workers to grueling conditions, low pay, and frequent abuse, leaving lasting scars on generations.

The Qing Dynasty’s response to the coolie trade evolved over time:

- Initial neglect: Early on, emigrants were viewed as traitors abandoning ancestral graves (背祖忘宗), unworthy of protection.

- Investigations and reforms: By 1874, figures like Chen Lanbin conducted pivotal investigations exposing abuses abroad, pressuring foreign powers like Spain to end the practice.

- Shifting attitudes: As remittances (银信) flowed back to China, returnees began to be seen as valuable contributors to local economies and potential allies in anti-Qing movements.

While too late for many victims, these efforts marked a turning point in recognizing the plight of Chinese laborers.

The legacy of the coolie trade is complex and multifaceted:

- Cultural preservation: Clan associations (会馆) and hybrid cuisines like Chifa reflect the resilience and adaptability of diasporic communities.

- Transnational identities: Descendants of coolies continue to forge connections across borders, preserving memories of their ancestors’ struggles.

- Memorialization: Efforts like Toronto’s Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial Park honor the sacrifices of those who contributed to global development.

- Family histories: Stories passed down through letters and oral traditions remind us of the human cost of the coolie trade and its enduring impact on families.

Victor Caso Lai’s journey to trace his roots exemplifies how personal discoveries keep this history alive.

To deepen your understanding of the coolie trade, consider exploring:

- Archival materials: Letters, contracts, and records preserved in village archives provide firsthand accounts of the experience.

- Historical sites: Visiting memorials, temples storing remains (公益金骨堂), or reconstructed ancestral halls offers tangible connections to the past.

- Scholarly research: Books and articles analyzing the economic, social, and cultural dimensions of the coolie trade offer comprehensive insights.

By amplifying these voices and stories, we ensure that the lessons of the coolie trade are not forgotten.

Steven

Roots of China was born from my passion for sharing the beauty and stories of Chinese culture with the world. When I settled in Kaiping, Guangdong—a place alive with ancestral legacies and the iconic Diaolou towers—I found myself immersed in stories of migration, resilience, and heritage. Roots of China grew from my own quest to reconnect with heritage into a mission to celebrate Chinese culture. From artisans’ stories and migration histories to timeless crafts, each piece we share brings our heritage to life. Join me at Roots of China, where every story told, every craft preserved, and every legacy uncovered draws us closer to our roots. Let’s celebrate the heritage that connects us all.